Special Edition: The Harlem Renaissance Style

With the 2025 Met Gala theme Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, this piece revisits the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance and traces the cultural impact of Black dandyism on fashion.

With the Met Gala just having taken place, I wanted to reshare this piece I originally wrote in 2018 for Shanghai-based Modern Weekly Style about the Harlem Renaissance. It was never published in English, and given this year’s theme, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, it felt like the right moment to revisit it.

At the time, I had the chance to interview Monica L. Miller, a key figure behind this year’s event and exhibition through both her academic studies and curatorial work. Her 2009 book, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, served as the primary inspiration for the Met’s theme and the accompanying exhibition at the Costume Institute, which she also co-curated. The piece includes several quotes from our original conversation.

This is a slightly updated version of the original. I wish I’d had more time to revise it, as some references may feel a bit dated, but it still offers plenty of compelling material on the Harlem Renaissance, Black dandyism and the cultural threads that continue to shape fashion today.

(And don’t miss the roundup of news and standout Latin American stars at this year’s Gala. Scroll to the end!)

During the Spring Summer 2018 menswear season, Grace Wales Bonner’s show notes featured excerpts from an essay by Pulitzer Prize-winning critic Hilton Als. The text explored the legacy of James Baldwin, the African American writer whose examinations of race, identity, and spirituality shaped mid-century American literature and continue to influence cultural discourse.

Wales Bonner also cited The Homoerotic Photography of Carl Van Vechten, a key chronicler of the Harlem Renaissance whose portraits captured the intellectual and artistic energy of 1920s Black America. As a designer known for her intellectual explorations of menswear—particularly as it relates to Black male identity—it is clear why the New York of the 1920s would captivate Wales Bonner.

Set against the backdrop of the Roaring Twenties and the Jazz Age, the Harlem Renaissance reshaped African American history, transformed New York’s cultural landscape, and left a lasting mark on the world. It was a moment of rebirth, one that cast the Black American community as a vital force in literature, music, theatre and visual art.

Dressing A New Identity

This gave rise to a new way of dressing, which Monica L. Miller, Associate Professor at Barnard College and author of Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, describes as “an aspiration of a different way of being that honoured and created Black style traditions and creativity.”

“Stylin’ out” in the 1920s, or dressing up, came from a range of impulses. One was the Great Migration, which began in 1916, as African Americans left the rural South for cities like Chicago and New York, drawn by industrial work opened up during the First World War.

“Harlem was specifically magnificent, with wide avenues and broad sidewalks,excellent grand apartments,” says Miller. She recounts that the diverse group of African Americans who gathered in these urban areas for the first time "meant people dressed up to signal their new opportunity, their potential new lives, away from a rural-based proletarian life.

Contemporary menswear still draws from 1920s style, continually reinterpreted throughout the 20th century.

Single and double-breasted suits with high buttons and notch lapels were common, often paired with strong shoulders, pinstripe trousers and fitted vests. These silhouettes were captured in James Van Der Zee’s portraits of Harlem Renaissance figures like Marcus Garvey, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Countee Cullen, which helped define the era’s visual language.

“Dressing well was part of a campaign to express to the world that Black people were on the cutting edge of modernity.”

At the Cotton Club, a wealthy white crowd drawn to Harlem nightlife was served by Black waiters in red tuxedos and entertained by music legends like Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Louis Armstrong and Cab Calloway. The latter helped popularise the flowing zoot suits of the 1940s, especially striking on the dance floor.

The suits were embraced by Malcolm X, jazz musicians and young Black and Latino people in cities; in 1943, the Zoot Suit riots broke out when U.S. service members attacked Mexican American and Black “zoot suiters” in Los Angeles.(NYT)

“Harlem in the 1920s was an area in which self-confidence and independence was fostered for Black people as individuals and as a community,” says Miller. Dressing well, she adds, was both about impressing others and earning recognition within the community. “It was part of a campaign to express to the world that Black people were on the cutting edge of modernity.”

Literature, Art and Radical Collaboration

The segregation and repression of the Southern states had long stifled Black cultural expression. The Harlem Renaissance opened new space for creative exchange, where editors, writers and artists collaborated and published work on an unprecedented scale.

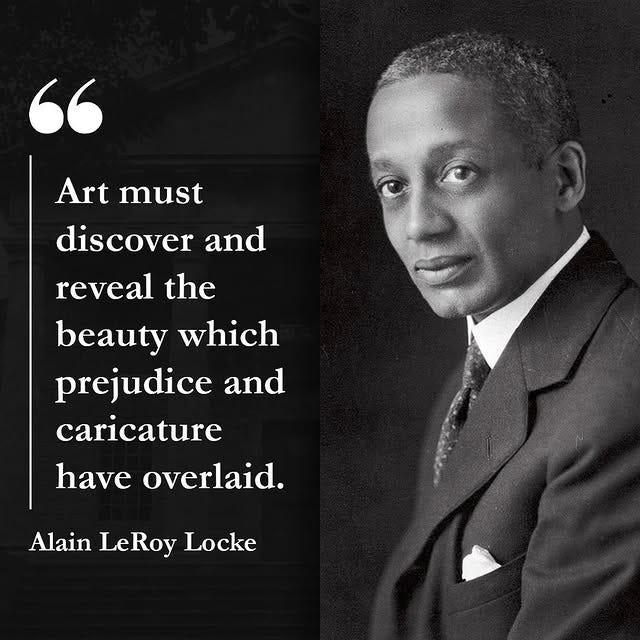

Participants sought to redefine their relationship to heritage and to one another. This vision was captured in The New Negro by Alain Locke, considered the leading voice of the Harlem Renaissance. Locke called for “race pride” and “stimulating race consciousness,” declaring that through art, “Negro life is seizing its first chances for group expression and self-determination,” with Harlem as the centre of a “spiritual coming of age.”

Langston Hughes championed the creation and appreciation of Black art on its own terms, without aspiring to “whiteness.” His groundbreaking work, rooted in lived experience, established him as one of the most influential poets in American history and continues to shape writers and thinkers today.

Also at the core of the movement was Wallace Henry Thurman, who, alongside Hughes and Richard Nugent, launched the literary magazine Fire!!. The publication brought together leading voices of the time, including Zora Neale Hurston, Gwendolyn Bennett, John Davis, Aaron Douglas, Arna Bontemps and Countee Cullen.

Fire!! was one of many examples of the cross-disciplinary collaboration that defined the era. Literary works were often accopmpanied by photography, illustration and design in magazines like The Crisis, Opportunity and The Messenger, or in poetry collections such as Sterling Brown’s Southern Road and James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones, both featuring art by Aaron Douglas.

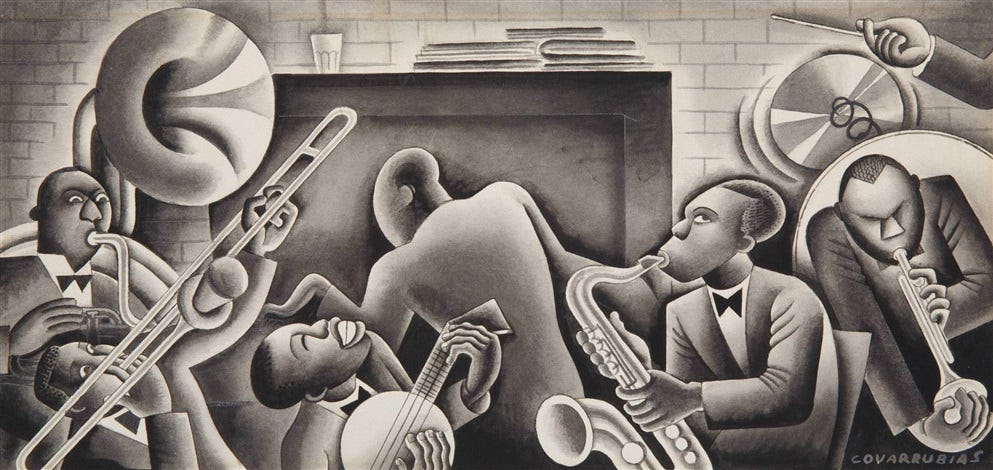

Books by Hughes, like The Weary Blues, featured covers by Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias, while Countee Cullen’s Color included illustrations by Charles Cullen.

Aesthetic Tensions: Du Bois and the Purpose of Black Art

Leading sociologist and civil rights activist William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was a vocal critic of some Harlem Renaissance ideals. He believed Black art should be used to advance social equality rather than reflect the harsh realities of African American life. Du Bois co-founded the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and served as editor of its publication, The Crisis, from 1910 to 1934.

“The height of popularity with jazz music created the perennially cool image of the Black man,” said writer and professor Jabari Asim, who was editor of The Crisis when he spoke to Mashable in 2015. He pointed to musicians like Dexter Gordon, Hank Mobley and Lee Morgan, who helped carry that image forward after the Harlem Renaissance and became household names.

From Political Empowement to the Rise of Hip-Hop

Asim also noted that during the civil rights movement, polished Black suits and crisp white dresses became a way to show dignity and challenge racist stereotypes. “They used clothing to show they would be as productive citizens as any whites if given rights,” he said.

Emmett Price, author of Hip Hop Culture, added that Black men have long used fashion to express pride and resistance, from dashikis in the ’60s to Afros in the ’70s and rap in the ’80s.

Both the Harlem Renaissance and the hip-hop movement opened space for a richer, more complex understanding of the African American experience, challenging prevailing stereotypes. Each gained broad, cross-cultural followings and continues to shape global culture today.

Dapper Dan and (some of) Harlem’s Style Modern Inspirations

A prime example is 1980s hip-hop outfitter Daniel Day, better known as Dapper Dan, who drew attention in 2017 when Alessandro Michele, then creative director of Gucci, allegedly copied one of his designs. During the brand’s Cruise 2018 show, Michele presented a fur-panelled jacket with balloon sleeves, nearly identical to a version Day created in 1989 for Olympic athlete Diane Dixon.

Day became known for his Harlem boutique on 125th Street, a favourite among artists like Big Daddy Kane, Eric B and LL Cool J. That same year, Kim Jones cited him as an influence for the bootleg aesthetic of Louis Vuitton’s Autumn.

Harlem Fashion Week, co-founded by Yvonne Jewnell and her mother Tandra Birkett, gives emerging designers a platform outside the official New York Fashion Week schedule. In September 2024, it marked its 13th season.

Brandice Daniel launched Harlem’s Fashion Row in 2007 to support and spotlight Black designers. It remains a key force in the industry and held its 17th Annual Style Awards in September 2024. Past supporters have included Mary J. Blige, Tracee Ellis Ross, June Ambrose and Dapper Dan.

Harlem’s style legacy remained a reference point well into the late 2010s. In spring 2014, Edward Enninful reimagined two Prada store windows with a 1920s Harlem-inspired set. In autumn 2018, Alexander Wang staged his show at the Hamilton Theater, and in January 2019, Stella McCartney presented her pre-fall collection at the historic Cotton Club.

“Harlem is my home,” says Guy Wood, CEO of 5001 FLAVORS and Harlem Haberdashery,ns with his wife Sharene. Both were born and raised in the neighbourhood. “It’s more than a place, it’s a source of inspiration,” he says.

Wood has dressed stars like Jay-Z, The Notorious B.I.G., and Jennifer Lopez. Looking at photos from the Harlem Renaissance, he sees confidence. “Men were dapper to compete with other men,” he says, noting how that energy helped shape fashion.

“Dandyism is a kind of time-travelling aesthetic in that it recognises the past,

comments on the present, and attempts to image a restriction-free future. I think this was as true in the 1920s as now,” says Miller.

NEWS

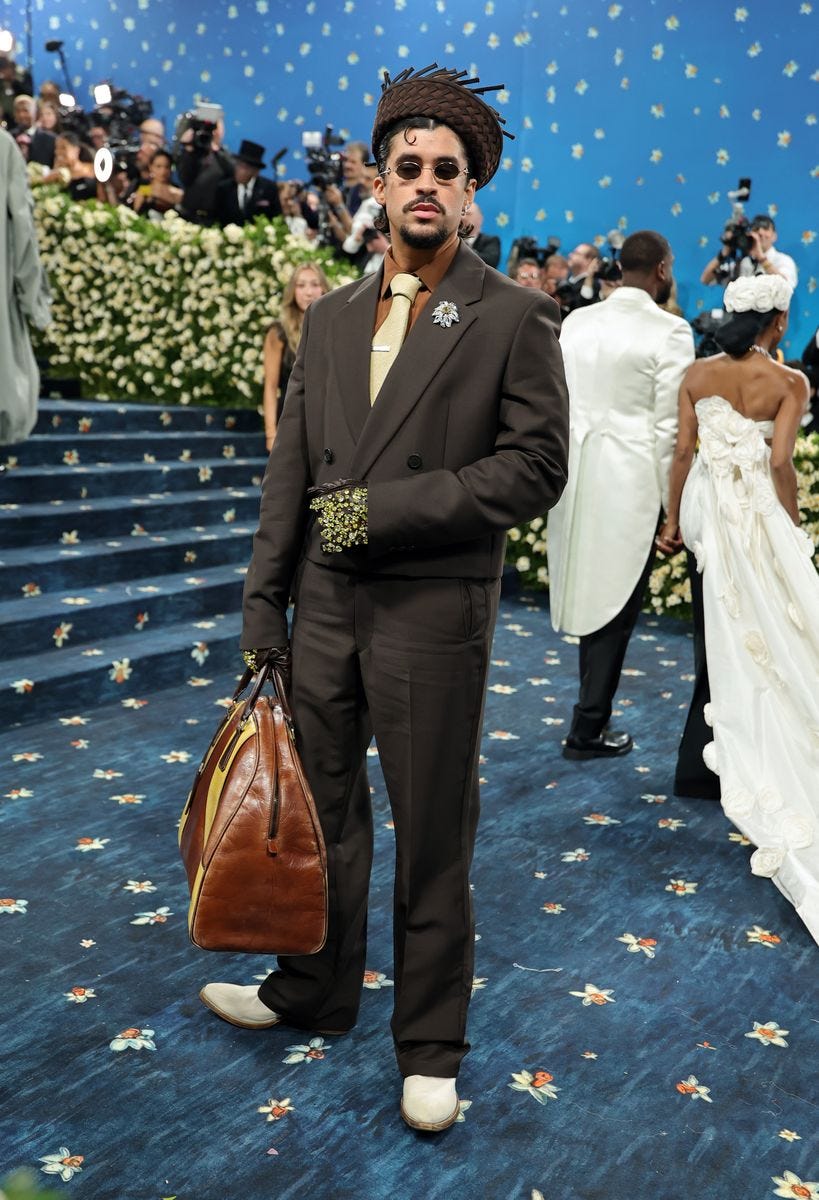

Latin American Stars at the Met Gala 2025

Shakira, Bad Bunny, Maluma, Willy Chavarria, J Balvin, Jenna Ortega and Omar Apollo were among the standout names who graced the flowered carpet of fashion’s main event.

To see the full list of stars at the Met Gala, click here.

Vogue Brazil marks its 50th anniversary with a commemorative May 2025 issue that departs from the magazine’s traditional format. The 236-page special edition features in-depth conversations between 56 figures who have shaped Brazilian fashion and culture, exploring themes such as identity, creativity, diversity and politics. Instead of fashion, beauty and lifestyle sections, the issue focuses on intergenerational dialogue, pairing influential voices across sectors.

The seven covers feature Anitta with Sonia Guajajara, Ney Matogrosso with Carlinhos Brown, Xuxa Meneghel with her daughter Sasha Meneghel, Luiza Brunet with Rita Carreira, Andrea Dellal with Sabrina Sato, Caroline Trentini with Isabeli Fontana, and Erika Hilton with Silvia Braz. Head of Content Paula Merlo describes the issue as a reflection on the magazine’s evolution and continued relevance in a rapidly changing cultural landscape.

Bogotá Fashion Week returns from 19 to 23 May with a standout edition spotlighting over 140 Colombian brands, from emerging designers to some of the most established names in Latin American fashion. Led by director Rebeca Herrera, the week will feature 25 runway shows and a series of panel discussions curated by Latinness, aiming to foster dialogue around the region’s creative and cultural impact.

Amiri appoints Mexican boxer Saul “Canelo” Alvarez as ambassador. The American fashion brand has partnered with the athlete who has held world championship titles in multiple weight classes. [BoF Inbox]

Thank you for making it this far! I will be back next week with more stories, ideas and discoveries from across the region.

Until then, take care and stay inspired.

Graciela.

GEN33 is a reader-supported publication. If you're liking it, tell a friend (or five).

Loved this article and the research behind this!